|

Lady GagaA Dissenting Opinion

In "Benefit of Clergy," George Orwell describes Salvador Dali as "an exhibitionist and a careerist, but he is not a fraud." Dali's artistic talent was enough to make him an "illustrator of scientific textbooks," but his egoism needed greater tribute. In absence of genius, Dali found fame by always doing what would "shock and wound people," allowing him to seem more original than he actually was. One confronts a similar phenomenon in Lady Gaga. She is not a fraud; she has more talent than most of her detractors or peers; still, one doubts if she is more than a pop star to "just dance around to." As Time magazine observed, Lady Gaga's act is not about her music or even her outfits; she "has become famous by being obsessed with fame." Obsession is not a talent. Is Gaga the musical equivalent to an "illustrator of scientific textbooks," a Britney Spears who can write and sing? It is impossible to prove any answer to this question. Taste and emotion cannot be disputed. Right and wrong do not apply to art, outside of verifiable facts. There is no objective way to prove Beethoven's Ninth Symphony better than "I Saw the Sign." One can only present evidence, and assert a conclusion. What has Lady Gaga brought––to culture, to music, to fashion, to life––that is new? Where has she gone where none have gone before? Put Ecclesiastes aside and try to answer this question; it's not a malicious one. It's striking how little of what Gaga does provokes genuine outrage, even in the gossip columns; Björk's swan dress was more controversial than any Gaga outfit. This essay argues that Lady Gaga's appeal lies in her lack of originality. Her weirdness threatens no one. This allows the viewer to have a "transgressive" experience without being required to think. Gaga's act purports to be about many things, but at bottom it satisfies the commmon demand that "every artist...shall pat [the viewer] on the back and tell them that thought is unnecessary." All else is marketing. Theft or Imitation?

Gaga apologists point out that art is theft. Every artist borrows from others, not always with attribution or acknowledgment of debt. This is true, but they forget Lionel Trilling's distinction: "Immature artists imitate. Mature artists steal." The word "imitate" comes from the Latin word "imago," meaning "image." To imitate something is to copy its image, without the substance or value to back it up. A counterfeit coin, for example, might be a likeness of the real thing, but it does not have the value of a real one. An homage is "a special honor or respect shown publicly." The word comes from the medeival Latin word "hominaticum," a word which originally denoted a ceremony where a vassal declared himself to be his lord's "man." An homage implies respect, deference and acknowledgment of debt, not just to the artist but to art itself, to a divine principle or some extrapersonal creative force.

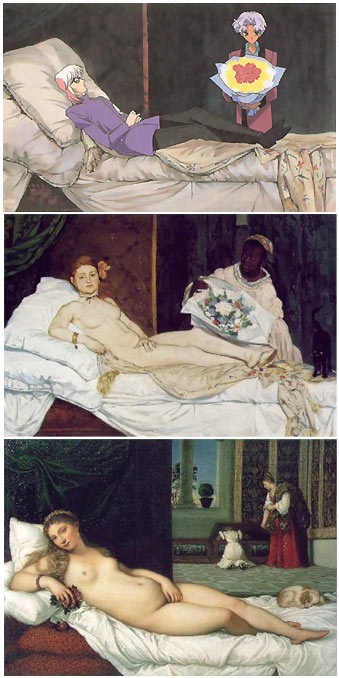

You respect no one by watering down a great work of art. A skillful homage is done so the viewer feels enlightened, not cheated, when they see it. The Man Who Wasn't There To steal successfully, you must add value to whatever you steal. When bands cover another artist's song, they don't make an exact replica of the original. The most successful covers are so well done, nobody cares that the band "copied" the song and lyrics from another. No one thinks Ella Fitzgerald a "copycat" when she sings songs by Gershwin, Weil, Porter and other composers. If she sang in imitation of some other singer, many people would. Every great artist has a style, a stamp of creative personality, which suffuses their best work. This style, this stamp, separates imitators from honorable debtors. The EvidenceThis section presents common complaints against Lady Gaga. Someone from Oh No They Didn't, a livejournal community for celebrity gossip, posted a long montage of similar outfits worn by Róisin Murphy, an Irish dance-pop singer, and Lady Gaga. The similarities are striking:

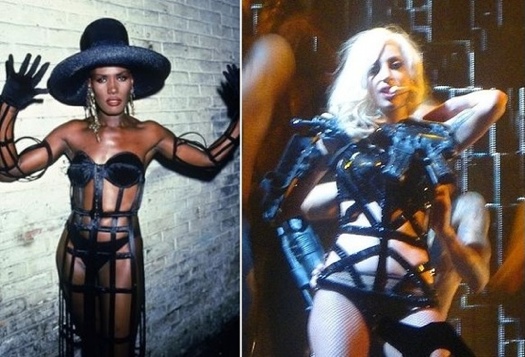

To see the whole chart, click here. A similar chart comes from here. Grace Jones, the Jamaican singer and model, is another obvious influence. Jones diplomatically said "I wouldn’t go to see her...I’d just prefer to work with someone who is more original and someone who is not copying me, actually." A few photos show Gaga wearing outfits almost identical to ones worn by Jones, decades earlier:

One collage shows Lady Gaga wearing the same clothes as Kelis, an R&B singer from New York City.

An "internet war" has flamed up on sites like Youtube, Twitter and Tumblr over whether Christina Aguilera copied Lady Gaga, or vice versa. Since Christina Aguilera has been a celebrity for over a decade, it would be more noteworthy if none of their outfits or hairstyles were similar. Similar videos have sprung up for how Lady Gaga copies Madonna, Britney Spears, and other long-standing pop stars. See the next to last sentence. Here is a video, though, in case you're curious: Youtuber ireallylikeyou compared and contrasted "I'm So Happy I Could Die" with Natasha Bedingfield's "Pocketful of Sunshine." The melody, backbeat and lyrics are substantially similar: A recent song, "Alejandro," strongly resembles the song "Don't Turn Around" by Swedish band Ace of Base. The rhythm and melody are nearly identical; the song's plots are also similar, about a breakup which happens despite continuing love. Youtuber Exantin69 took the song "Girl Next Door," released by Darin in 2007, and synced it up with the video for Lady Gaga's "Just Dance," released in 2008. They match: M.I.A., a Tamil/British singer, criticized Lady Gaga's songs for sounding like "20-year-old Ibiza music." From an interview: People say we're similar, that we both mix all these things in the pot and she spit them out differently, but she spits them out exactly the same! None of her music's reflective of how weird she wants to be or thinks she is...She’s not progressive, but she’s a good mimic. She sounds more like me than I fucking do!Lady Gaga plugged multiple products in the "Telephone" music video, including a hamburger. To M.I.A., this indicates that the music industry isn't "even interested in making money from music anymore." Joanna Newsom voiced a similar, but more detailed criticism, in the Guardian: [L.G.] just happens to wear slightly weirder outfits than Britney Spears. But they're not that weird––they're mostly just skimpy. She's fully marketing her body/sexuality; she's just doing it while wearing, like, a 'fierce' telephone hair-hat. Her sexuality has no scuzziness, no frank raunchiness, in the way that, say, Peaches, or even Grace Jones, have–– she's Arty Spice!In the same interview, Newsom posited that "Her approach to image is really interesting, but you listen to the music, and you just hear glowsticks." Jihan Forbes, a contributor at Starpulse.com, stated that "Lady Gaga is in some ways a reincarnation of Elvis Presley: She takes cues from other truly forward-thinking and innovative artists of color, and repackages it so that white America can comfortably digest it." At Racialicious, a website on "the intersection of race and pop culture," one reader commented: To combat the lack of message in her music is really Gaga’s ultimate weapon: the way she panders to her fans, her “little monsters”. She includes them in on [sic] her charade in a way that no one does, overly praising them on Twitter while penning vague platitudes about living life to the fullest and never giving up. However strong and subversive she may appear in public, she plays coy and victimized to her fans who then feel it is their duty to love and defend her. It’s basic and people fall for it like hotcakes. Examining the Evidence

[These days] it is the unassuming storyteller who is reviled, while mediocrities who puff themselves up to produce gabby "literary" fiction are guaranteed a certain respect, presumably for aiming high...It is as easy to aim high as to aim low. Isn't it time we went back to judging writers on whether they hit the mark? It does not much matter if Lady Gaga stole these looks, and songs, or if they are organic products of her imagination. Nor does it matter if she is self-manufactured or a puppet of her handlers. Every similarity on the above list could be an innocent coincidence, and the conclusion would be the same: Lady Gaga offers nothing new. For all her sequins, bubbles, baubles and bras, Gaga is predictable in her outrageousness. Black and white patterns, see-through lace, big blonde updos, shoulder pads, faceted mirrors, sunglasses, fishnet stockings, wide-brimmed hats––the same elements recur in her outfits with clockwork regularity. None of these elements were startling 20 years ago, even 40 years ago; why would they be so now? As for her off-stage antics: the U.S. President also partied, used cocaine and had premarital sex (no word, though, on any bisexual dalliances). The summer before Gaga's first album dropped, a song called "I Kissed a Girl" reached the Top 40. Even Gaga's causes celebre––gay rights and AIDS awareness––are hardly controversial for a dance-pop star.

Gaga's performance, like a "strip-tease act conducted in pink limelight," is one of mass entertainment's many odes to itself. Simultaneously safe and exciting, mass entertainment aims to "cajole, seduce and flatter customers to let them know that what they thought was right is right." It repackages, sands down and glosses over the unpleasant side of life. The customer's comfort, tastes and instant gratification are "of utmost concern." Thus, consumers––the real product––are sold to retail companies through advertisers, market researchers, and other intermediaries, who play on the "deeper strata of their [i.e., our] emotional nature." The genius of the Lady Gaga persona, or performance art piece, or whatever you want to call it, is this: it is able to be "shocking" in such a way that it offends no one. In one interview, Gaga wore a jacket of sewed together Kermit the Frogs, to protest the wearing of fur. What could possibly be a less cutesy, or less oblique, way to protest? Gaga claimed it was to "get people to think about [how fur is made]." Absent this comment, all anyone would think about is her. Other performance pieces––fake blood, biting the heads off Barbie dolls, an "intersex" rumor––may make some inchoate "cultural commentary," but they make the viewer focus on the artist, not the art. This is what makes Gaga so popular: her act seduces and flatters her followers, reassures them of their edginess and offers them self-love––even a peak experience––even, vicariously, fame––for the price of a lipstick, a compact disc or a concert ticket. Put another way, her little monsters––the real product––are sold to various retailers (iTunes, Ticketmaster, t-shirt companies) by her persona. In some oblique way, the Lady Gaga persona analyzes this relationship. What does that change, especially when the analysis is so anodyne?

Like all good postmodernists, the more forcefully Gaga asserts her genius, the greater her genius is; the more her act mirrors pop culture, the more "devastating" its commentary; whatever reaction she inspires, from love to loathing to deconstruction, is the correct one and the point of the persona. Fans can always invent some tortured defense of pretentious mediocrity by appealing to emotion, vague obfuscations and ad hominem attacks, since anyone who refuses to see such glittering brilliance is clearly a bumpkin––or, worse, an elitist. One is reminded of B.R. Myers's "Ten Rules for Serious Writers," a tract which exhorts writers to "sprawl," "equivocate" and "mystify: If you sound smart...then you must possess a brilliant mind." Her act also has an element of Sammy Glick So what? That's marketing. Marketing is dull-normal for a pop star. "The Merchants of Cool" confronted this issue almost a decade ago. Other musicians have done what Gaga does, better and more explicitly; Lily Allen's "The Fear The three qualities that Lady Gaga unquestionably possesses are intelligence, a gift for singing and hyperbolic self-confidence. "I know my greatness is individual," she said in a recent interview, "And I want every woman to be able to say that." This statement sounds xeroxed from the self-esteem movement, a popular ideology when Stefani Germanotta was a child. And suppose you have been told from birth how unique you are; suppose your identity, and the identities of your peers, are of the utmost importance to an entire industry, since before your first orgasm. How then can you know yourself? There is always one answer: through others. Always do the thing that will gain attention. Charm and flatter people, appeal to the deeper and "more psychotic" strata of their emotional nature. If you succeed, the mask may stick to your face, even become it. Succeed wildly, and the public will make a huge imago in your image. Your romantic lie may, through great effort, become one which others hesitate to correct or disbelieve. Along these lines you can always feel yourself original and important. After all, it pays! It is much less scary than real life. Through the eyes of others you may glimpse the scope of your accomplishments; in private, cosmic loneliness may confront you; in public, "haters" may irritate you and try to throw your stride. It is a sure bet some of your critics are jealous, petty and vindictive; given enough influence, these characteristics may be attributed to all of them. In this way reputations are built and empires expanded, and much of the top crust of humanity has its way with the rest. On a global scale, one pop singer is benign, especially if she serves as a "gateway artist" to more talented ones. The real Lady Gaga––if such a person can be said to exist––may possess splendid personal qualities. Her music is not more than ordinarily bad. The real question is why this is considered transgressive, not just by her little monsters but by apparently intelligent members of the public. Most people have a simple explanation: culture has been deteriorating for so long, anything a hair outside the mainstream is lauded as revolutionary. But one would still like to know why culture has been deteriorating, and, even more importantly, how this deterioration can be stopped. Related Reading: 10 Weird and Wonderful Women Musicians (Who Eat Lady Gaga For Breakfast) Riot Grrrl Style, Fashion and Self-Expression The Best Punk Models You've Never Heard of References: "A Contrarian View of Lady Gaga." From Racialicious. Retrieved May 18, 2010, from http://www.racialicious.com/2010/05/05/a-contrarian-view-of-lady-gaga/ The Big Lie. In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved May 10, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Lie Biles, Jeremy. "Lady Gaga's Secret Religion." In Religious Dispatch Magazine. Retrieved May 11, 2010 from http://www.religiondispatches.org/archive/culture/2637/lady_gaga%E2%80%99s_secret_religion_/ Celeste. "Mikage, Manet and Titian." From Empty Movement. Retrieved May 20, 2010 from http://ohtori.nu/analysis/06_celeste_mikage_manet_and_titian.htm Orwell, George. "Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí." Retrieved May 15, 2010 from http://www.orwell.ru/library/reviews/dali/english/e_dali Return to Enjoy Your Style's style icons page. Return to Enjoy Your Style's home page. Search Enjoy Your Style: |

Search this site: